What Does Terry Rodgers Want?

By Jim Zimmerman

While nearly a generation of American painters dismissed the opportunities available to someone with a keen appreciation for finely rendered figurative painting applied to social and psychological observation, Terry Rodgers has been quietly perfecting his skills, and the results can be seen in a stunning show of 10 large paintings at Louis Stern Fine Arts in Los Angeles.

Rodgers is an accomplished painter with a striking mastery of light and transitions, who presents large, intricately designed works on canvas filled with beautiful people in extraordinary settings. And he can draw like few other artists with any vision these days. The combined force of his vision, with the lines of the figurative drawing, the architectural complexity of figures and objects, and the harsh and beautiful varieties of light, make this a show that will trouble your imagination--and maybe your conscience.

These are not just pretty pictures. In fact, the first reaction can be the opposite-that there is something alarming about a canvas bursting with interesting faces and enigmatic gestures. Who are these people? They appear dislocated and disaffected, as well as too beautiful and too cool. Your initial reaction could be alienation, or even anger, and the suspicion that you've been thrust against your will into the role of voyeur at a very exclusive private party you'd rather not attend.

But something does look familiar. It might be the hunted look on one face, the isolation of a nearby figure, or the twisted discomfort of yet another stunningly drawn human form in the background. Look more closely, let the scene settle, and you might feel a sympathetic little shock of recognition in the subtle details of posture, gesture, and glance. There are mysteries lurking in each canvas, mysteries of mood, motive, and relation. Above all, you come up against the individual's tentative quest for identity, purpose, commitment, and authenticity in a world founded on the ideology of uncertainty and chock-full of seductive distractions.

In the moment of each of these large paintings, there is a convergence of character and situation that speaks to the challenge we all face in a world of unrelentingly refined and sophisticated surfaces. Rodgers makes us ask questions about the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that we feel. Each of us envisions nobility for ourselves, so why do we continually run up against such staggering vulgarity?

The show adds up to an electrifying insight into the dissonance of collective material comfort and individual, personal discomfort. We do not wish to be in this picture, even as we do not wish to miss any opportunity like this. This is what everyone apparently wants, and yet, having it, no one is happy-they are stuck, frozen, trapped, as it were, "beside themselves" with petty anxieties. In a world characterized by masses of refugeesand immigrants, the people Rodgers shows us so intimately have "arrived," and there is no place left for them to run.

Aided by his masterly drawing and treatment of light, each painting is also a brilliant architectural conception, bursting with interesting images, and yet there is an undeniable emptiness that cries out to be filled. This seems to be what Rodgers intends, and he has been probing this emptiness throughout the years of what we now see as America's innocence and ease. Rodgers shows us a haunted innocence and a shocking unease that collides with superficial elegance and barely suppressed egomania.

"As I look at these pictures all together," he said recently in his studio, "they seem to pose the question, 'What's missing?' When you have everything on the surface, where do you find what is satisfying?"

Rodgers speaks of the tension between the exterior selves that complex people create to present to others and the uneasy awareness of these projections clashing with the interior selves that remain unconvinced, uncommitted, and inchoate.

Of Buying Time, Rodgers observes, "It's always time to buy something even as a way of staving off something else. What is it that's being avoided?"

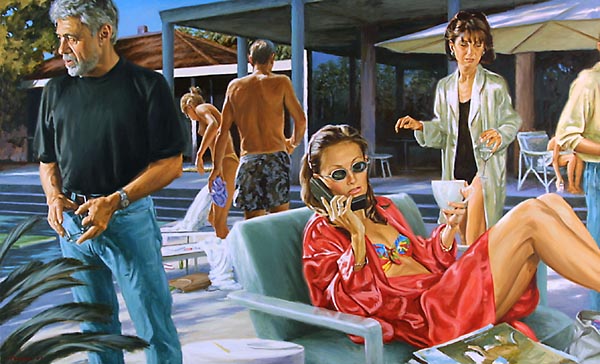

In The Right Moment, an apparently perfect situation is undermined by the subtle sense of everything being, as Rodgers says, "a little on edge." He points to the girl lying on the chair at the right as the clearest indication that things are not as wonderful as they seem.

The painting is both an outdoor scene and a very full interior psychological space, Rodgers notes, referring to the woman drinking coffee, the door, the mountains, the umbrella, the evergreens, and numerous other eye-catching objects. "It's such a complex space," he says, "too open to be a maze, but very complicated."

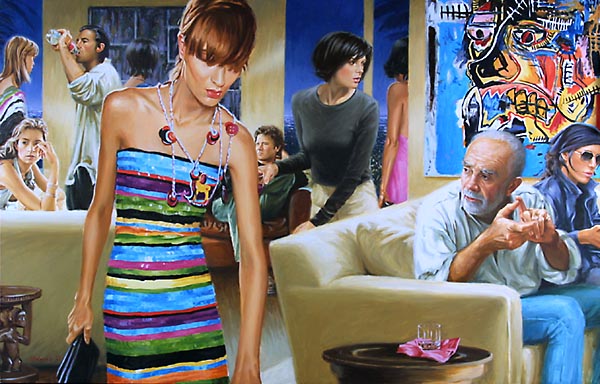

Rewriting the Book is an extraordinarily stark interior scene with many figures in close proximity. Rodgers has used two pieces of art to illuminate the superficially laid-back L.A. scene, one a brightly colored, psychologically tormented Basquiat, and the other a quiet abstract expressionist work which seems more in keeping with the veneer these people express, even as a sinister undercurrent of manipulation and exploitation insinuates itself.

"Art appears in many of my paintings," Rodgers says. "I don't make a distinction among any of the arts people live with and through--the hairdos, the clothing, the art on the walls, the house itself. Even people's postures and gestures have a sort of acquired artfulness."

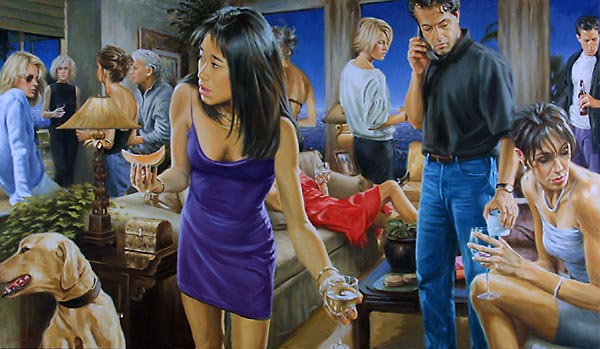

Another distinctly L.A. scene is depicted in Something She Said. The two principal figures in the painting seem connected in some way, and yet they are absolutely apart at the moment. The woman is one of those rare Rodgers' figures who seems purposeful, engaged, and present--but on the telephone. The man, perhaps a partner or an enemy, is clearly alone, though only a few feet away, and turned completely inward. This simultaneous relatedness and disconnection is emphasized by the striking light.

"When the light is beginning to wane and you have these great porticoes," Rodgers says, "the painting is suffused with murkiness. The male figure and the swimmers are the only ones in bright light. With the others, something is filtering the light. It struck me that having this combination of personal opacity and a dark world sets up a suggestion--and perhaps a sympathy--about what might be in their heads."

The Glass House is one of Rodgers' less disturbing scenes. It was inspired by a photograph he saw in a magazine.

"The house seemed to have a life of its own," says Rodgers. "In my imagination, as people appeared in the setting, I found them comfortable and at close quarters, and yet despite the grandeur of the space, it suggested questions to me like, 'How do we live with each other?' and 'What do we do?'"

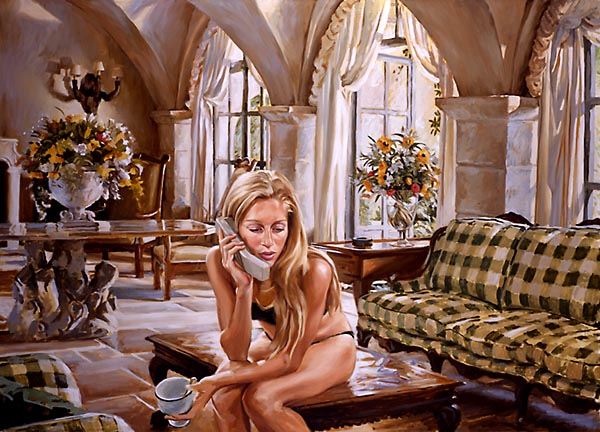

He Sees It Her Way is less benign and more pointed. Two young people seem to have everything, but the extraordinary setting is once again the occasion for questions.

"What is it that makes life worth living?" Rodgers reflects. "That's where illumination comes from, asking these questions."

Or, when you get to a perfect place, as Rodgers does in so many of his paintings, what do you find there, and what is left to find anywhere?

In The Opacity of Light, Rodgers' ideas and his love of the complexities of light are central.

"There's the deception of beauty and light," he observes. "We tend to think they mean goodness and well-being, and we're constantly being taken in, just as we are always at the risk of being taken in by appearances."

Welcome Interruption plunges us into a green world dominated by two figures, the young woman in the foreground--with qualities in her mouth and eyes that Rodgers finds "revealing"--and the central standing male figure, whose facial surfaces, Rodgers says, seem to show the man's inside, "like an x-ray."

All of these paintings are dramatically rendered in color, light and shade transitions, and what Rodgers calls the vectoring of objects and persons. The vitality of each situation is built out of painterly brush strokes that are supple enough to be effective but not so perfect as to take the roughness out of these dynamic constructions of social and personal realities.

Rodgers has been quick to make new technology work for him. David Hockney's recent argument concerning the methods of composition employed by painters of centuries ago involving available technology (lenses back then) makes perfect sense, given the working methods Rodgers employs. Whereas Hockney makes the case for projection to aid drawing, Rodgers has emphasized the richness of the conception. Taking advantage of the most recent technology to painstakingly compose his paintings, Rodgers continually experiments with every aspect of the complex image on a computer before taking his ideas to the canvas. Every little detail is perfected in his mind before he attacks the project in the studio.

Rodgers' work is a psychological exploration and a cultural interrogation. It demands that we look, and look long and hard, and it forces us to answer questions not only about the scene we are struggling to understand, but also about the motives and purposes that make our lives matter.

2002