Pause / Focus

By Emiel van der Pol, Art historian

Lulls in language define the rhythm of human thought. Instants of silence in a sequence of signs are necessary to form a coherent framework for inner dialogue and in turn, self-awareness. Without silence, words wouldn't make sense. Furthermore, language itself is bound to a body. A train of thought chugs along from brain to lips on tracks shaped by expanding and contracting lungs and veins. Even the voice in our head takes a pause to breathe. All the frames per second flashing before our eyes, all the beats per minute, all the effects of all the drugs and all the booze don't adhere to this natural rhythm. Still, we crave these distractions and we can't turn away. There is tremendous appeal in things that make one depart from personal cadence. They can prolong silence to achieve a meditative state, or remove pauses altogether for an exciting cacophony. Meaning is made elsewhere, but perhaps it's fine to be adrift.

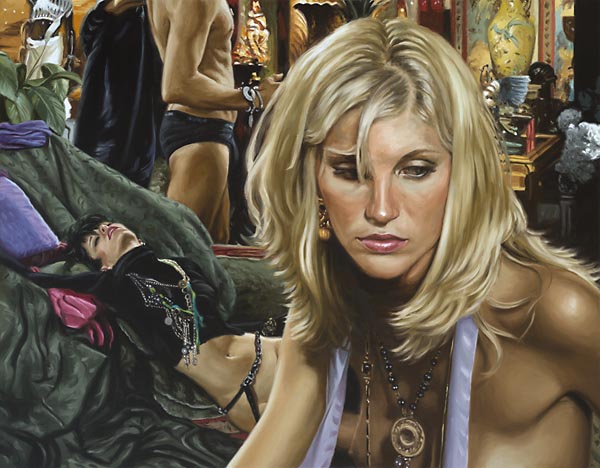

In his paintings, American artist Terry Rodgers has comparable power over time and space. He can expand or condense it at will. He lets the representations of his models float and flow into an ambiguous vectorial space adorned with lush fabrics and baroque ornaments. In his latest work, the models seem to be in stasis, caught in an instance of silence. As if they vaguely remember the end of the last word they thought or heard and are now eagerly awaiting the start of a new one. They want to connect but are unaware of their surroundings. Their well-toned bodies stand slouched or lie draped over expensive looking furniture. They hover above their surroundings as much as they reside in proximity of them. The shimmer on their skin makes them seem distant, luxurious, ethereal. Their expressions are captured in a transitional state, an introspective moment between the striking of one pose and the attempt at another. They feign nonchalance but in fact care deeply about their posture and presence.

Half dimmed eyes vacantly observe whatever is going on outside of the frame. There is a vague outward momentum at the core of these pieces, as if everyone is waiting for their cue to leave the scene. A cast without a script, waiting for a director to arrive while the camera is running and the lights are blazing bright. Look more closely, and even the coherence of the scene itself starts to fall apart. These bodies don't touch each other, these minds aren't aware of other presences. Light and shadow are expertly used to create the illusion of unity. But in all probability that chandelier was never in the same room as that chair, these people have never met each other and the skyline seen in the windows is borrowed from another day and place. They are all isolated elements, bound together by thin layers of paint and brains that still prefer the world as a sensible whole.

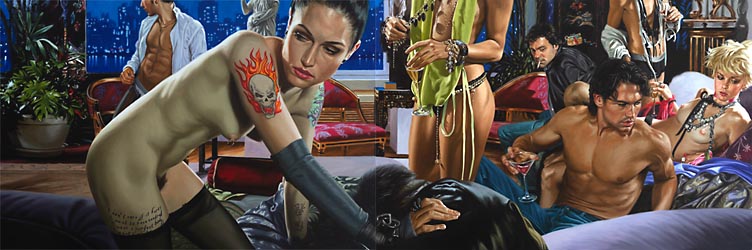

It is hard to pinpoint these scenes to a certain period or culture. They reveal very little in terms of contextual clues. Instead, they seduce the viewer with lace, gold and fur. Heavy fabrics overlap with shiny metals and smooth skin. There's an open bar and comfy chairs, but if you start asking questions you're out in a heartbeat. Sometimes, a brand logo or tattoo deliberately breaks this spell of timelessness. These alterations stick out like a sore thumb and harshly pull the piece into a current time stream. The flaming skull and masochistic power trip inked on the central figure of You Were Never Really There are prime examples of this effect.

But who's to say that those tattoos were on those particular patches of skin? As a cultural phenomenon they are definitely associated with permanence and individuality, but in painting everything is constantly interchangeable. When seen in the broader context of these works, the tattoos seem to represent an ironic template for individualism. Defining yourself through signs meant to be seen by others. In these paintings they share a picture plane with intricately patterned fabrics and ornamental curls on golden candelabras. They have become part of a swirling mass of gilded movement. Especially in large-scale works like the aforementioned You Were Never Really There, and the monumental Shadow of Delight, one can feel empathetic with the subject's existential fatigue and their sense of entrapment in their made-to-fit cages of luxury.

Over the years, Terry Rodgers has built a vast archive of attractive surfaces. After decades of photographing gorgeous people and shiny baubles, he is now in possession of a digital treasure trove of eye candy. The point of origin for each of these pieces can be found in the scale-less, vector-based playground of image editing software. Here, he freely mixes and matches elements into frantic compositions. While photographing, he made sure that the props he used couldn't be dated. So models, poses, accessories and backdrops can be repeated throughout Rodgers' oeuvre. However, they are always reconfigured into new constellations. This repetition of elements emphasizes the weightless vacuum from which they were born. They have become symbols to describe social processes, while gradually losing their link to the original individuals captured by Rodgers' camera.

This process is perhaps most visible in the pieces Facial Recognition and The Golden Hour. In dense, complex compositions Rodgers applies a set of flattened layers in which he place his figures. The resulting structure resembles those used in image editing software. His virtuoso technique allows him to paint objects with weight and volume while simultaneously accentuating their edges. They are flat when viewed as a whole, but have substance when seen on their own plane. Every element in the scene wants to take center stage. They all pulsate in an exciting push-and-pull dynamic. The end result is a surface crackling with energy, even if everyone depicted on it carries themselves with heavy, tired eyes. Rodgers wants to draw attention to the in-between. The exact physical and mental location where things become permeable and where light, hope and doubt can briefly reveal themselves.

In All the King's Men, End Note and Eve in her Garden, a sudden shift in scenery has occurred. There is a lot less baroque opulence on display. Sleek, reflective surfaces have taken the place of Persian rugs and heavy curtains. Instead of a forward and outward momentum, the figures seem to have found an isolated place to sulk for a while. The backdrop here isn't a fragmented collage of rich surfaces. Rather, it forms a muted, blurred whole of purple, blue and pink hues. Colours that stand in stark contrast with the vulnerably lit individuals roaming amongst them. A remarkable focus on transparency is shared amongst these three works. The glasses are empty and the chill of night is allowed to enter the room through massive panes of glass. The party seems to be over and what remains is the sense that something was lost, perhaps for the better.

Especially End Note and Eve in her Garden seem to convey a wry kind of consolement found in evening-borne isolation. In a sense, these works can be seen as the elegy for their predecessors. They capture the moment of reflection that can ground an individual anew. Even in places that have no significance, no distinguishable link to one's character, there is a chance to make a connection when traveling inwards. Through his representations of the jet-lagged set, Terry Rodgers seems to want to make clear that it is not love, purpose or happiness that makes one human. It is the need for these things, and the long wait before one arrives there that does. He describes an emotional limbo, a constant existential flux as an acceptable state of being.

The aptly titled All the King's Men shows faces hanging on to the last threads of consciousness. They are still too drunk to reflect, but the realization that actions have consequences is slowly seeping through their inebriated membranes. They hesitate to take another sip, wondering if they want to prolong this daze or want to drift into another. The figure with the black scarf covering his eyes has already made his choice. Behind him there is a rare sight in Terry Rodgers' work; a dark figure turned away from the viewer. Someone seems to be looking out of a window, perhaps to ponder the night's sky. He has also made his choice: to step outside of the spectacle and to observe it for a while.

All the narratives mentioned here seem to culminate in The Shadow of Delight. It is a true feat of painterly prowess, an engulfing vortex of sensual bodies and enchanting decorations. Everything is on the surface while everyone stands alone. Meanwhile, all the bodies on display mechanisms to cope with existence: a few tattoos, some nipple piercings and ample glasses of champagne. They hardly manage to find their footing and stumble from pose to pose. Behind them the lush scenery menacingly fades into absolute darkness.

2018