The Apotheosis of Pleasure — December 2006

The Apotheosis of Pleasure

And, while he slaked his thirst, another thirst

Grew; as he drank he saw before his eyes

A form, a face, and loved with leaping heart

A hope unreal and thought the shape was real.

Spellbound he saw himself, and motionless

Lay like a marble statue staring down.

— Ovid, 'Narcissus' in Metamorphoses, IIIi

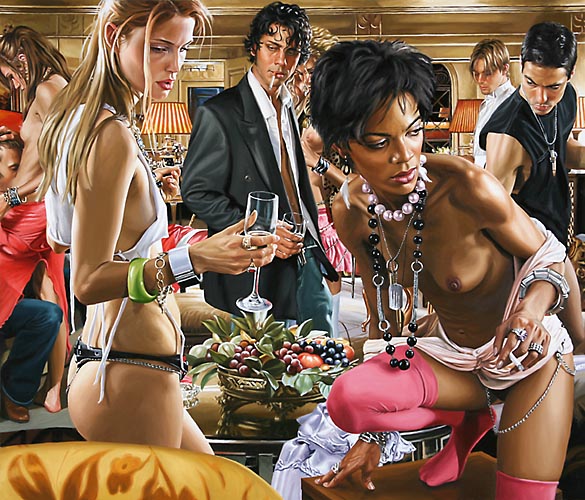

If the private get-togethers of today's privileged have ever constituted the object of one of your own fantasies, the paintings by US artist Terry Rodgers will surely challenge your imagination. For, what does it mean to be successful today and how do we understand pleasure anyway? Contemplated from a certain distance, Terry's depictions of the upper-classes' leisure life seem to open windows onto this paradise-like place Charles Baudelaire celebrates in his famous poem the Invitation to the Voyage:ii

There, nothing is but grace and measure

Richness, quietness and pleasure.

Slumped in finely embroidered fabrics, promiscuous beings wear heavy jewels and lift expensive liquors to their lips; their mouths imperceptibly open as though to speak. Yet the spell slowly vanishes as we shorten the distance that separates us from the canvas –those three secular steps that bring us closer to its surface. The outlines irremediably dim and the precious materials transform into aggregates of brushstrokes and paint. Terry Rodgers' world is that of appearances, the wealth of which is primarily that of the art of painting.

It is therefore no surprise to hear that one of Terry's first memories relates to a portrait by Diego Velázquez, and that later he became fascinated by the seemingly effortless brushwork of the impressionist painters and some of their heirs. As with the seventeenth century Spanish master, these latter also favored colors over outlines. Terry's work equally displays that primacy of pure painting and the importance of lines in structuring the compositions rather than in shaping objects and human figures. As Velázquez and Edouard Manet, Terry's special dexterity in manipulating the brush turns the canvas into a sophisticated optical instrument. Two levels of perceptions coexist without ever coinciding. As Ludwig Wittgenstein's famous example proves, just as the viewer cannot see the image of the duck and that of the rabbit at the same time, (s)he cannot simultaneously see both the form and the paint that shapes it.iii

However this play of optical illusion is not confined, in the case of Terry's work, to the use and application of colors. It also involves the compositions which, on the one hand, invite us to take part in the scene while, on the other, dissuade us from doing so, hereby setting the marks for a visual dialectical process. Often, Terry places a repoussoir figure in the foreground which leads our gaze straight to the dead center of the composition. Likewise, the backgrounds create what seems to be a geometrical space. Yet at the very heart of the composition, bodies literally fill in the space. Intertwined they form geological strata rather than sketch a space according to the laws of optical perspective. The room we are invited to enter is not a replica of the physical world. Instead, it describes a social and a psychological one, graphically revealing the limited nature of some human relationships and suggesting an altered time experience.

This tight human nexus offered to our inquiring gaze constitutes one of the most striking and appealing aspects of Terry's work. However, is it possible here to speak about intimacy? In which way does Terry's work articulate nakedness and sexuality? In a pornographic manner as some have argued? One must remember that the nude portrait –and pornography itself—hasn't always taken the same form nor served the same cultural purpose. For instance, it was not until the nineteenth century that the nude became a genre on its own having been subordinated to the representation of literary scenes. Terry's work, similar to that of Edouard Manet's Luncheon on the Grass (1863), capitalizes on this very modern representation and thus scandalizes the contemporary bourgeoisie as much as it mirrors the evolution of its taste. That said, what at first sight primarily differentiates Terry's work from present-day pornographic productions is the lack of graphic references to the sexual act. Today, surrender, physical perfection and equivocal situations characterize not only pornography, but permeate the world of media and advertising. As, for instance, Jeff Koons, Marc Quinn and the Chapman brothers do, Terry appropriates and stages key elements of the media's visual rhetoric in order to more acutely reveal the obsolescence of the myth of capitalist well-being that they support. Terry's paintings function like fun-house mirrors, whose distorted reflections still serve to reveal certain hidden aspects of reality.

It is therefore set against the backdrop of cultural theories that Terry's paintings most fully reveal their meaning. There is something pornographic about the experience of human relationships governed by the laws of market economy and about contemporary manners that turn sexuality and the private sphere out into the public realm so as to better profit from them. According to the French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, the survival and control of modern society depend on a politics of individualized pleasures and on the valorization of an exhibitionist behavior. In the midst of a system that incites individuals to stage and to enjoy the public exposure of each and every bit of their everyday life, Terry's nudes express less the idea of nakedness than that of their visibility. Likewise, the opulence and material wealth become less the signs of a successful lifestyle than obstacles to happiness. Stimulated by an order of rewards and immediate gratifications, individuals willingly engage in a system that seems to answer their wishes, when in fact they are merely drawn further into a structure of compliance and extortion. They are disciplined to become both the object and instrument of their own submission; they have become themselves a part of the very power that controls them. This inevitably engenders a powerful feeling of both alienation and fear.iv

In this world of wealth, the survival of which depends on its subjects' obedient consumption, individuals are reduced to harboring superficial human relations. Fallen prey to desires that neither bodies nor available luxury seem to satisfy, each of the beings that crowd Terry's paintings is self-centered –the body on display and the gaze introverted. They all seem to have crafted their appearance so as to render it as sleek, chic, and delectable as possible. From their being only a marketable image remains, the one which will give them their life credentials in what Guy Debord has named the Society of the Spectacle.v This “lonely crowd,”vi whose impoverished existence Debord theorizes, is depicted by Terry with as much virtuosity as the rest of the objects congesting the scenes. In this way, the painter draws a direct –material—parallel between objects, bodies, pieces of furniture and, last but not least, the famous “family jewels,” which shapes are more often insinuated than shown. Everything, according to this world order, is exchangeable and, ultimately, everyone has stopped enjoying each other's and one's own beauty. Even the promise of intimacy has lost its attractiveness to the contemporary individual turned frigid and to whom the American social critic Christopher Lasch refers as “the new narcissist.”vii

Exclusively talking with him or herself, each of these atomized beings is devoted to a religion that does not soothe his or her distress. Terry Rodgers gives us a taste of these ritual gatherings –festivals sans festivity—where participants seem to have abandoned life as a meaningful experience, and replaced it with a material enterprise. Petrified by the power of their own stare, they have become the lifeless idols of an era driven by consumption.

The genealogy of the representation of individual distress and private devotion primarily points at martyrdom and ecstasies in the realm of religious writings and, in every other kind of literature, at expressions of love and fear related to the encounter with death. In the visual arts, each epoch has favored a specific rhetoric of facial expressions and bodily gestures that conveyed these extreme experiences as exemplification of that era's norms and values. Terry Rodgers observes and stages an array of postures and attitudes that characterize the principles that order our contemporary lives. As seventeenth century saints were looking up towards God and at a promised afterlife, contemporary (fe)male narcissuses look down towards the murky pool of their own earthly purgatory –the purgatory that is one's own egoism. For both Terry and the great masters before him the body is a medium through which to show what happens beneath the skin. Hence, this visual archaeology leads us much beyond the nineteenth century French salon painting of which Terry's grandes machines remind us immediately. They span different genres, time periods and media. Terry's anxious bodies have as much in common with Gianlorenzo Bernini's sculptural group Santa Theresa in Ecstasy (1647-1652), Chaïm Soutine's work and the Narcissus (1598-1599) by Caravaggio as with The Romans of the Decadence (1847) by Thomas Couture. Likewise, his invented private gatherings would have perfectly fit in the best-seller, American Psycho, the story of a serial killer who treats his peers like lambs to slaughter.viii Terry's raptures are private ecstasies deprived of their promised redemptory pleasures.

In a system that turns bodies into merchandise, and merchandise into fetishes, the exaltation of pleasures and open sexuality can only function as trompes-l'oeil. Terry's work takes its roots in this very reality. Thanks to a brilliant technique and the help of elaborate compositions, his work tempts us into believing in the appearance of things in order to better unveil their artificiality. For in fact, the bodies disciplined in the name of Beauty and Wealth that crowd his paintings look like an army –a war machine—that never rests. Weapon and target of their own oppression, we can almost hear the ticking of their anxious hearts about to burst. Because, when the search for pleasure becomes a life principle, and satisfaction, an ethical requirement, it is paradoxically happiness and individual freedom that are taken away from us. The price we pay to deify pleasure – isn't it the exile of our own body put in the service of a transcendent cause that keeps it enslaved? The Apotheosis of Pleasure above all refers to our astonished and wondering gaze under which forms take shapes or decompose according to the distance, the attention and the perspective. Thanks to his display of bodies, what Terry Rodgers highlights is the flesh of the painting that, in its turn, offers the image of what remains out of sight: the tensions that underlie contemporary life.

2006

http://www.cameralittera.org/?page_id=13

ii Charles Baudelaire, Les Fleurs du Mal (1868), (Paris : GF-Flamarion, 1991) pp. 99-100. (My translation)

iii Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, tr. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1953), p. 194 (II.ii).

iv Michel Foucault, Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (1971), tr. A. Sheridan (London: Penguin Books, 1991); The history of sexuality (1976-1984), tr. R. Hurley (London : Penguin Books, 1990).

v Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967), tr. Black & Red (1977) online at http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/debord/society.htm

vi Idem

vii Christopher Lasch, The culture of narcissism, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978).

viii Bret Easton Ellis, American psycho : a novel, (New York : Vintage Books, 1991).